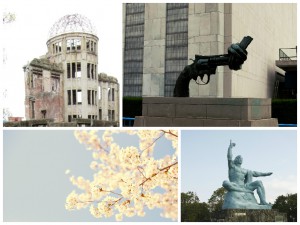

70th Anniversary of the End of World War II

Magazines Covered This Month

Gaiko, Seiron, Sekai, Chuokoron, Bungeishunju

◆ September 2015 ◆

Shinichi Kitaoka, “The stance Japan should take on colonial rule and aggression,” Chuokoron, September issue

Yasuhiro Nakasone, “The last testament of a former prime minister,” Bungeishunju, September issue

Kan Kimura, “Considering issues as part of the ‘present,’ not the ‘past,’” Chuokoron, September issue

Sumio Hatano, “Historical issues and postwar diplomacy—the battle over ‘claim rights,’” Gaiko, Issue 32

Masaharu Shimokawa, “Has Asahi Shinbun repented for their misreporting on comfort women?” Seiron, September issue

■ Points of Debate Over the Statement on the 70th Anniversary of the End of WWII

■ Points of Debate Over the Statement on the 70th Anniversary of the End of WWII

On August 14, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe released a statement on the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII, with Cabinet approval. Before writing the statement, the Advisory Panel on the History of the 20th Century and on Japan’s Role and the World Order in the 21st Century was established this year by the prime minister, and he used their report for reference when writing the statement. Shinichi Kitaoka, the Deputy Chairman of this panel and International University of Japan President, wrote “The stance Japan should take on colonial rule and aggression” for the September issue of Chuokoron.

Dr. Kitaoka commented on the media focus on the four keywords of ‘aggression,’ ‘colonial rule,’ ‘remorse’ and ‘apology,’ saying “It is bizarre to use whether these words are included or not as a basis for judging the statement,” but nonetheless gave his own opinion that “However, how the past is perceived is an important issue. In that respect, I believe the key is ‘aggression.’”

Dr. Kitaoka clearly states that “There are some people who say that since there is no clear definition for the word ‘aggression,’ then Japan did not commit any acts of aggression. This is completely wrong…. No matter what standards you use, Japan clearly committed acts of aggression. For example, the Manchurian Incident…. As a result of the Manchurian Incident, Japan occupied territory several times the size of Japan, and established Manchukuo. Manchukuo included northern Manchuria, which Japan had never held any interests in before. It is absurd to try and explain this as self-defense. Self-defense assumes equivalency, and doing anything more is aggression.”

Another keyword is ‘colonial rule.’ In Japan, there is a trend to view Japanese modern history as a response to the colonialism of powerful Western European states, but Dr. Kitaoka denies this argument, writing “…of the many reasons behind entering the Pacific War, liberating Asia was never a primary factor. Most of the decisions were made to protect existing Japanese interests.”

Regarding the importance of historical perceptions, Dr. Kitaoka writes “Japanese people’s understanding of modern history is shockingly shallow, and this does not apply only to the youth…. The importance of joint historical research is also significant…. There is no need to force a common understanding of history, but if debates are carried out based on the evidence available, then exaggerated extremist views will be eliminated eventually.” However, he firmly states that “The vast majority of Japanese people alive today were born after the war. Japanese people today have no direct responsibility to bear. There is no need for the prime minister to apologize to other countries.”

He also lists seven points for “what can Japan do to help prevent conflicts around the world.” They are: 1) United Nations reform; 2) Economic aid; 3) Support for democratization; 4) Efforts to establish legal rules for resolving conflicts; 5) Increased international cooperation such as with peacekeeping operations; 6) Increased market liberalization; and 7) Strengthening of the Japan-US security alliance, which is a global public good. Dr. Kitaoka concludes “These points are based on Japan’s regret over its mistakes before the war. In the past, Japan challenged the international order, and caused its collapse. After the war, Japan developed as a beneficiary of international order. Moving forward, Japan should help support this order. In this way, regretting the past and creating the future are one and the same.”

■ An Elder Statesman’s Proposal

Former Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone (in office from 1982–1987), 97-year-old elder conservative statesman, admits in his article “The last testament of a former prime minister” in Bungeishunju that “The previous war, with the large number of victims it caused, was not a war that should have happened, and could be said to be a misguided war. It is understandable that people call it a war of aggression against other Asian countries.”

Touching on the fact that it became an international problem with China when during his term as prime minister he visited Yasukuni Shrine, where Class A War criminals are among those enshrined, he spoke on how complicated historical perceptions are for those who have experienced war. “It is difficult to have both pride in your people and learn from history. The Pacific War has been clinging to Japanese people like a mist. Really, Japanese people should have settled things with the leaders of that war themselves.”

In addition to the problem of historical perceptions, the Cold War and short-lived governments in Japan also contribute to long-term instability in Japanese politics, leading to important issues not being handled. As stability is slowly returning, Mr. Nakasone is hopeful that bold steps will be taken to deal with important issues.

In particular, he has his eye on the security bills. “I have always argued that limited use of the right to collective self-defense should be allowed based on a Basic Law on Security,” indicating an opinion close to the Abe government’s policy. He also spoke out on how the Diet is working, saying “…the government has to carefully explain what is meant by ‘limited,’ and clarify the degree to which it could be exercised. The government’s response is reflected by public opinion polls, and they should pay close attention to public opinion and citizens’ perceptions as they try to eliminate the concerns and doubts people have…. at the same time, some means to break free of the current stagnation is necessary.”

Regarding constitutional reforms, the biggest topic for Japanese politics after the war, the former prime minister praised the current constitution for being accepted by the populace and contributing to Japan’s postwar prosperity, but also argued “However, we also lost sight of many things during that time. As I mentioned before, not declaring unique Japanese values such as its history, traditions and culture is a major lack when it comes to the country’s constitution.”

He also spoke on economic reforms, saying “The tension between policies focusing on growth or on financial reform exists because they have such a large influence on the economy, and neither can be said to be entirely good or bad. However, the government must not let down its guard even if the economy is doing well, and must indicate a clear plan for fiscal soundness while looking at future economic trends.” In addition to arguing for fiscal discipline and continuing the trend of administrative and fiscal reform that Japan has been carrying out since Mr. Nakasone was in office, on the subject of educational reform he strongly supported the focus on history, culture and tradition that was in the revision to the Basic Act on Education nine years ago, saying “As globalization continues, there will be more people moving into and out of the country and interacting with each other. This will make Japan’s identity as a nation even more important.”

■ Postwar Diplomacy and Historical Interpretations

Of the historical issues Japan faces with other countries, South Korea is a special case. The September issue of Chuokoron has an article by Kobe University Professor Kan Kimura, titled “Considering issues as part of the ‘present,’ not the ‘past.’” Writing on why historical issues with South Korea are becoming more and more complicated instead of lessening or moving towards resolution, he says “What has changed over the past 25 years (in South Korea) is not the historical perception of what happened in 1945 or earlier, but the perception of the Japan-Korea Claims Agreement. This change in perception is also expanding in one direction, increasing the range of exceptions.”

The Agreement Between Japan and the Republic of Korea Concerning the Settlement of Problems in Regard to Property and Claims and Economic Cooperation was concluded in 1965 at the same time as the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea, and in it both countries confirm that any past problems from 1945 or earlier “have been settled completely and finally.” In the intermittent negotiations over the next couple decades, the issue of comfort women was never known to be discussed. However, from 1991 to 1992, the issue of “military comfort women” became an explosive diplomatic issue coinciding with South Korea’s democratization. However, unlike the military governments, Roh Tae-woo’s government was using democratization as its rallying call. By interpreting the issue as being an exception to the agreement, the government moved towards seeking legal compensation for former comfort women.

As citizen movements’ in South Korea became more active, this exception grew, and since 2010 Korean courts have made decisions seeking compensation from Japanese companies beyond the limits set by the government. In Japan, the government, courts, and public opinion all maintain the perspective that past issues have been settled completely and finally with the Japan-Korea Claims Agreement.

In order to break out of this stalemate, Mr. Kimura states that “…the only possibility is to use the power of people not involved in Japan-Korea relations, and have them change the situation.” It is possible to either establish the arbitral commission specific in the Japan-Korea Claims Agreement for when disputes occur over the interpretation of the agreement or to set up an international commission recognized by both governments as a place to debate from a position of freedom, without any binding force. “What is important is to once again create a situation in which the citizens of both countries and the political and judiciary elites that believe their country’s interpretation of the Japan-Korea Claims Agreement is right can confront the extremes of that debate, and by doing so debate flexibly in a situation removed from the constraints of laws and national face.”

An article written by University of Tsukuba Professor Emeritus Sumio Hatano in Gaiko Issue 32, titled “Historical issues and postwar diplomacy—the battle over ‘claim rights,’” states that historical issues in the postwar period stem from inconsistencies in the Treaty of San Francisco and claim rights.

Mr. Hatano explains that the Treaty of San Francisco was the basis for postwar Japan’s position in international society, and until the 1970s the legal frameworks for bilateral peace treaties and reparations agreements with Asian countries were as “peace treaties handling the outcome of the war.” He follows by saying “This peace treaty system never even considered individual reparations. This is because by both sides abandoning all claim rights, it was supposed to resolve everything including damages to individuals. In this way, the issue of postwar compensation was a challenge to the peace treaty system.” The most well-known example of this is the comfort women issue. Along with the democratization of South Korean politics that started in 1987, public opinion and citizen groups began to influence the debate over accounting for the past. Since the Takeshima issue also arose in 2005, the South Korean government and courts have begun to indicate opinions and decisions contrary to the stance that everything was resolved with the claims agreement. Regarding this movement, Mr. Hatano comments that “It will not immediately result in the claims agreement being abandoned, but the stability of the ’65 system is in an uncertain position politically and legally.”

The belief that past accounts have not been settled has also affected unexpected areas. Regarding the original report on “military comfort women,” former Mainichi Shinbun Seoul Bureau Chief Masaharu Shimokawa researched the source of the number of comfort women being tens of thousands, and found that the Women’s Volunteer Labor Corps mobilized in South Korea during the war had been counted as comfort women. “Since 1943, approximately 200,000 Korean women were mobilized in the labor corps, and of those 50,000 to 70,000 young, unmarried women were used as comfort women,” but Mr. Shimokawa claims that this number is unsupported. According to one researcher’s study, an article from August 14, 1970 in the Seoul Shinmun says “From 1943 to 1945, a total of approximately 200,000 women from South Korea and Japan were mobilized in the labor corps. Of those, 50,000 to 70,000 are thought to have been Korean women.” Mr. Shimokawa says “This story is about the labor corps, unrelated to comfort women,” but the problem is that it was read incorrectly and spread around.

*This page was created independently by Foreign Press Center Japan, and does not reflect the opinion of the Japanese government or any other organization.